MERCURY-ATLAS 7 MISSION REPORT |

||

LAUNCH DATA |

||

|

|

|

Launch |

24 May 1962. 07:45 Eastern Standard Time (EST) |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 14, Cape Canaveral, Florida, USA |

|

Launch Vehicle |

Atlas 107-D |

|

Spacecraft |

'Aurora 7' (MA-7); Spacecraft No. 18 |

|

Spacecraft Mass |

Approx. 1,349 kg (2,975 lbs) |

|

|

|

|

MISSION OBJECTIVE |

||

For the 2nd US crewed orbital space flight, the objectives included: further evaluation of the human/spacecraft system for three orbits; evaluation of the effects of space flight on the astronaut; obtaining the astronaut's observations on the operational suitability of spacecraft systems; evaluations of replaced or improved systems over previous missions; and further evaluation of the Mercury Worldwide Tracking network. The mission was also assigned a programme of scientific observations and investigations. |

||

|

|

|

CREW DATA |

||

Crew Position |

Name |

Mission |

Pilot |

M. Scott CARPENTER, 37 Lt-Commander US Navy |

1st |

|

|

|

Flight Crew |

1 |

|

Call Sign |

Aurora 7 |

|

Back-up Crew |

Walter Schirra |

|

EVAs |

None (none planned) |

|

|

|

|

MISSION DATA |

||

Flight Duration |

4 hours 56 minutes 5 seconds |

|

Distance Travelled |

Approx. 122,318 km (76,004 miles), completing 3 orbits |

|

Orbital Data |

160.7 x 268.4 km (99.8 x 166.8 miles), with a period of 88.5 minutes |

|

Landing |

24 May 1962, at 12:41 EST |

|

Landing Site |

Atlantic Ocean, 201 km (125 miles) north-east of Puerto Rico; recovery ship USS Pierce |

|

|

|

|

Mercury-Atlas 7 Crew Selection

On 4 October 1961, the crews for the first and second American orbital space flights were announced privately to the Mercury team. MA-6 would be flown by John Glenn, with Scott Carpenter as his back-up and supported by Al Shepard. MA-7 would be flown by Deke Slayton, with Wally Schirra as back-up and Gus Grissom as support. Gordon Cooper was not assigned directly to support either flight at this point. On this basis, it seemed reasonable to assume that Carpenter would fly on MA-8 and Schirra on MA-9, with Cooper flying MA-10. These assignments were announced publicly on 29 November 1961, during the post-flight press conference for the MA-5 two-orbit flight of 'Astrochimp' Enos earlier the same day.

However, a problem would surface in January 1962 that concerned a cardiac irregularity in Slayton's heart. This had first shown up during centrifuge tests in August 1959. Since then, medical experts at NASA and the US Air Force had reviewed the data and debated what effect a high-G flight on the Atlas might have on Slayton's heart. Despite pleas from his fellow astronauts that he should fly and a medical review to support this, the growing public interest in the man-in-space flights and concerns over a possible abort scenario at up to 21 G load meant that the decision was taken made not to fly Slayton in case the 'problem' developed further while he was in space. The very upset astronaut was grounded.

On 15 March 1962, it was announced that Carpenter would replace Slayton and fly MA-7. Schirra would remain as back-up pilot before moving on to fly MA-8, with Cooper coming in to serve as his back-up.

The contentious decision grounded Slayton for the next ten years, before he finally regained flight status and flew into space for his only mission in July 1975, as a crewmember on the American part of the Apollo-Soyuz mission. MA-7 would prove to be Carpenter's only flight into space as well.

With Slayton grounded, it would have been reasonable to assume that his back-up - Schirra - would have been the primary candidate to step in and fly the mission. However, coming so close to the planned launch date, team leader Walt Williams pointed out that with Carpenter having already amassed 79.5 hours pre-flight check-out and training time as back-up to Glenn on MA-6, he already had double the time in training than it would take to fly the mission. Carpenter was the best prepared because of the delays and lengthy preparation time that had been required to support Glenn's orbital flight. The decision to fly him would also allow Schirra more training time for his own longer mission later in the year.

During Mercury flight operations, the other six astronauts normally supported the one who was flying in some way. For the Carpenter flight, apart from Schirra performing the back-up role and Glenn who was fulfilling his post-flight assignments, the rest were assigned as Capsule Communicators (CapCom) at tracking and communication centres around the globe: Grissom remained at the Mercury Control Center at the Cape in Florida; Shepard was in California; Slayton went to Muchea, Australia; Cooper was sent to Guaymas, Mexico.

The Mission

The flight of John Glenn in February 1962 had proven the Mercury-Atlas system capable of supporting an astronaut in orbit for a few hours. Having pioneered the launch processing and mission preparation timeline - and with Glenn having demonstrated that the astronaut could be more than simply a passenger - it was decided that Carpenter would be given more control in flight during the next mission. He would be able to manoeuvre the spacecraft around to observe sunrise and sunset, as well as using the horizon, landmarks and stars to aid navigation. Medical investigations were designed to evaluate the astronaut while orientating the spacecraft in orbit, to determine any disorientation he might feel. According to the official NASA Mercury history, "The next Mercury mission [Carpenter's] ought to be as much of a scientific experiment as possible, not only to corroborate MA-6 but also to explore new possibilities with the manned Mercury spacecraft." There was a desire to include a few purely scientific experiments and observations in the flight plan for MA-7, to yield a greater degree of scientific data rather than the engineering data the earlier flights had concentrated on. By April 1962, five experiments had been selected:

The mission would still be flown for three orbits and would not be extended to six, despite the added scientific experiments.

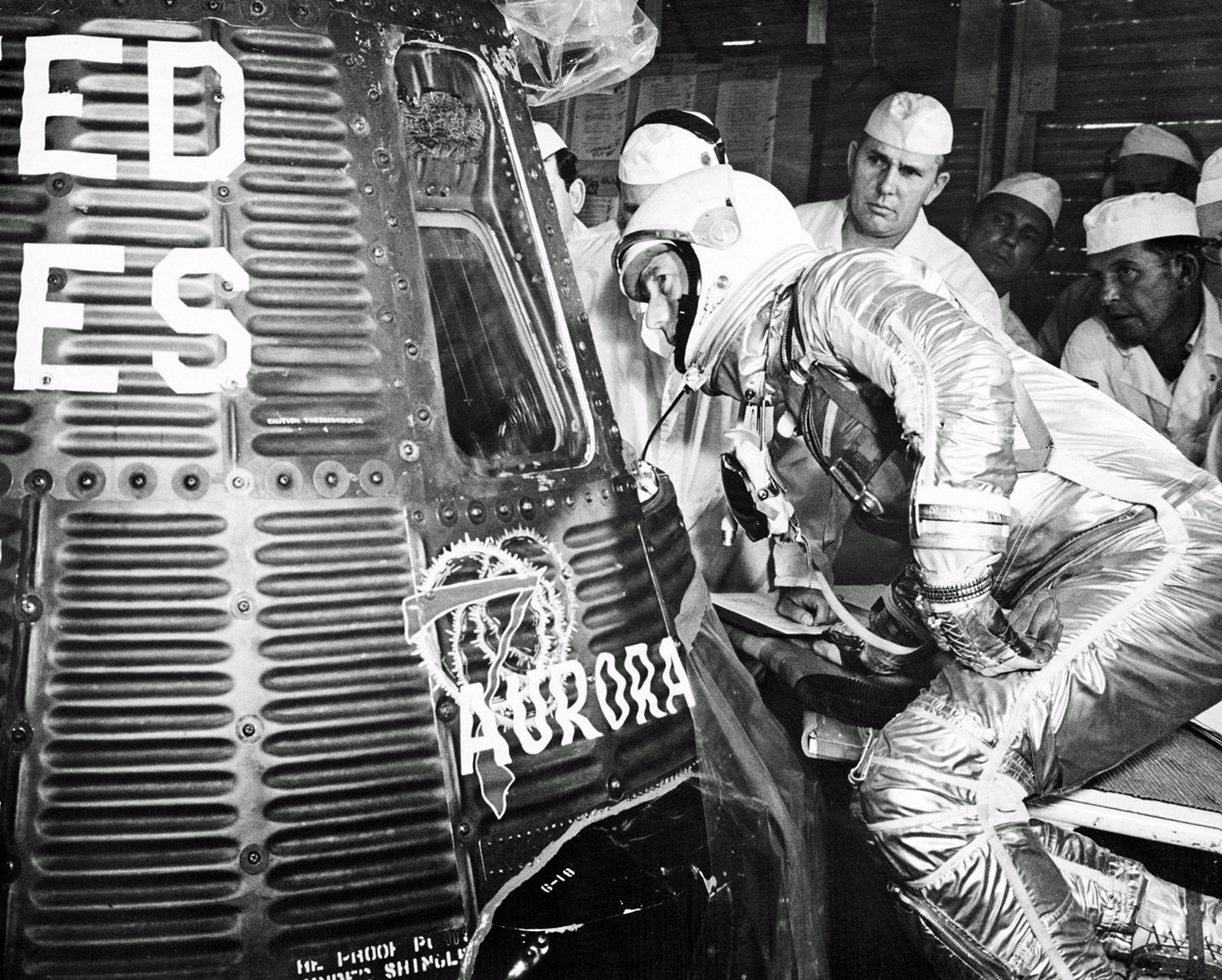

Launch Phase

Hardware for the flight had begun arriving at the Cape six months before the mission. The capsule (serial number 18) arrived first on 15 November 1961. When he was assigned to the flight, Carpenter named the capsule 'Aurora 7', which he chose because "I think of Project Mercury and the open manner in which we are conducting it for the benefit of us all as a light in the sky. Aurora also means dawn - in this case, the dawn of a new age. The '7', of course, stands for the original seven astronauts."

The Atlas (serial number 107-D) arrived at the Cape on 8 March 1962. Over the next few weeks, independent and combined systems testing was completed on the booster and spacecraft before they were mated for launch. Check-out problems with the spacecraft and launch vehicle delayed the intended original launch date of the second week in April until almost the end of May.

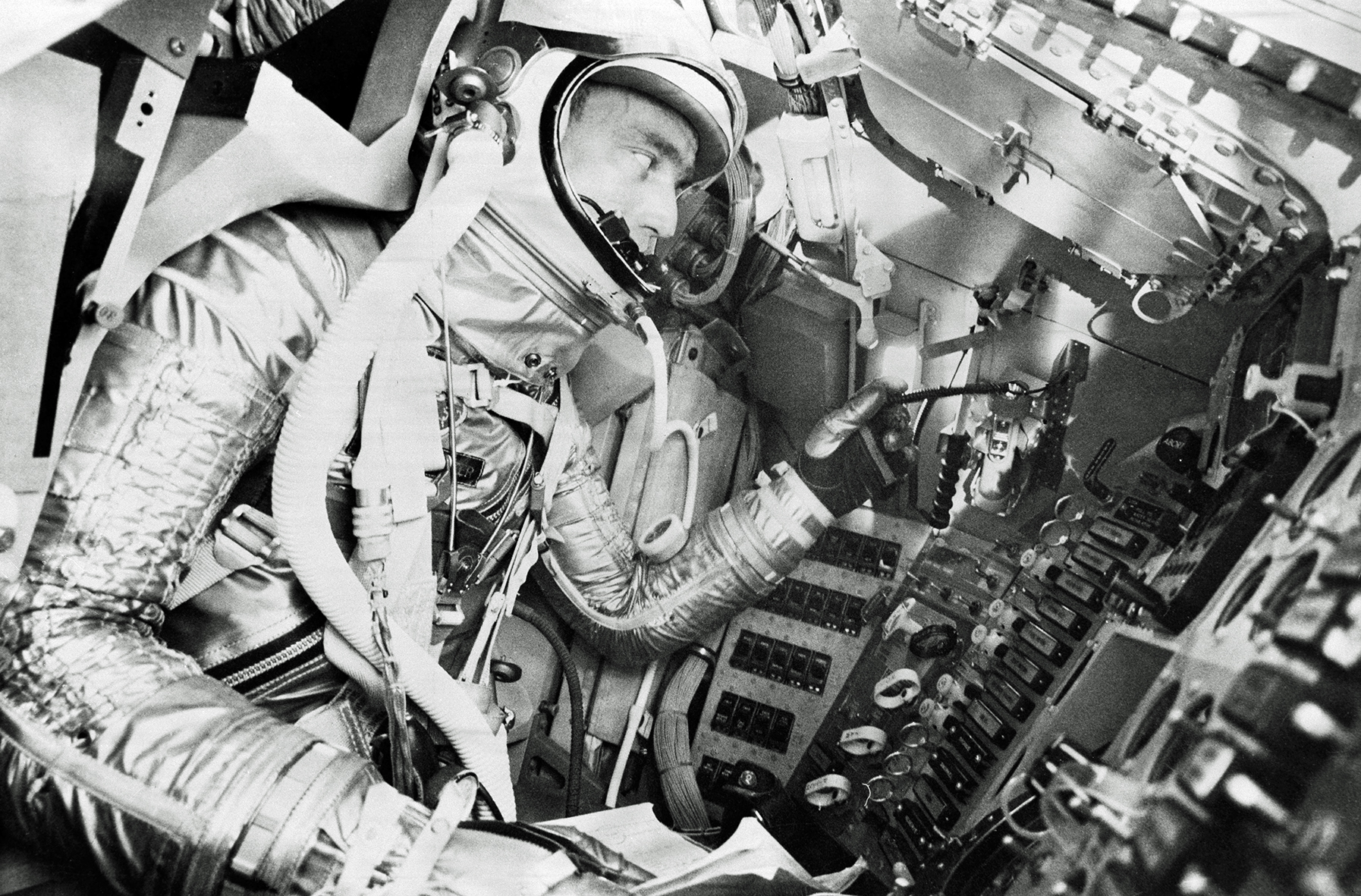

It was an early morning wake-up call for Carpenter in the crew quarters of Hanger S at Cape Canaveral. Over the next four hours, the astronaut ate breakfast, had a physical examination, dressed in his pressure garment and journeyed to the pad. He was placed inside the spacecraft just before 05:00. The countdown was one of the smoothest to date, with only a persistent ground fog and cloud cover slightly hampering the pre-launch procedures. Small, 15-minute delays for additional camera coverage put the planned launch time back from 07:00 to 07:45. In the intervening time, Carpenter became thirsty and sipped some cold tea from his squeeze bottle supply. He also chatted with his family, who were watching proceedings from the viewing area.

Lift-off occurred at 07:45 on 24 May 1962. The Atlas lifted off the pad carrying the second American astronaut into orbital flight, witnessed by an estimated audience of 40 million on TV in additon to those at the Cape. Inside the spacecraft, Carpenter had expected a much louder ascent and was surprised at the relative quietness of the launch, with little vibration as the aerodynamic stresses increased after staging. He could see the sky outside turning a darker blue and felt a jolt as the escape rocket jettisoned. As the Atlas separated from Aurora-7, there was a gentle drop in the acceleration forces and Carpenter was soon reporting his elation at achieving orbital flight.

Orbital Operations

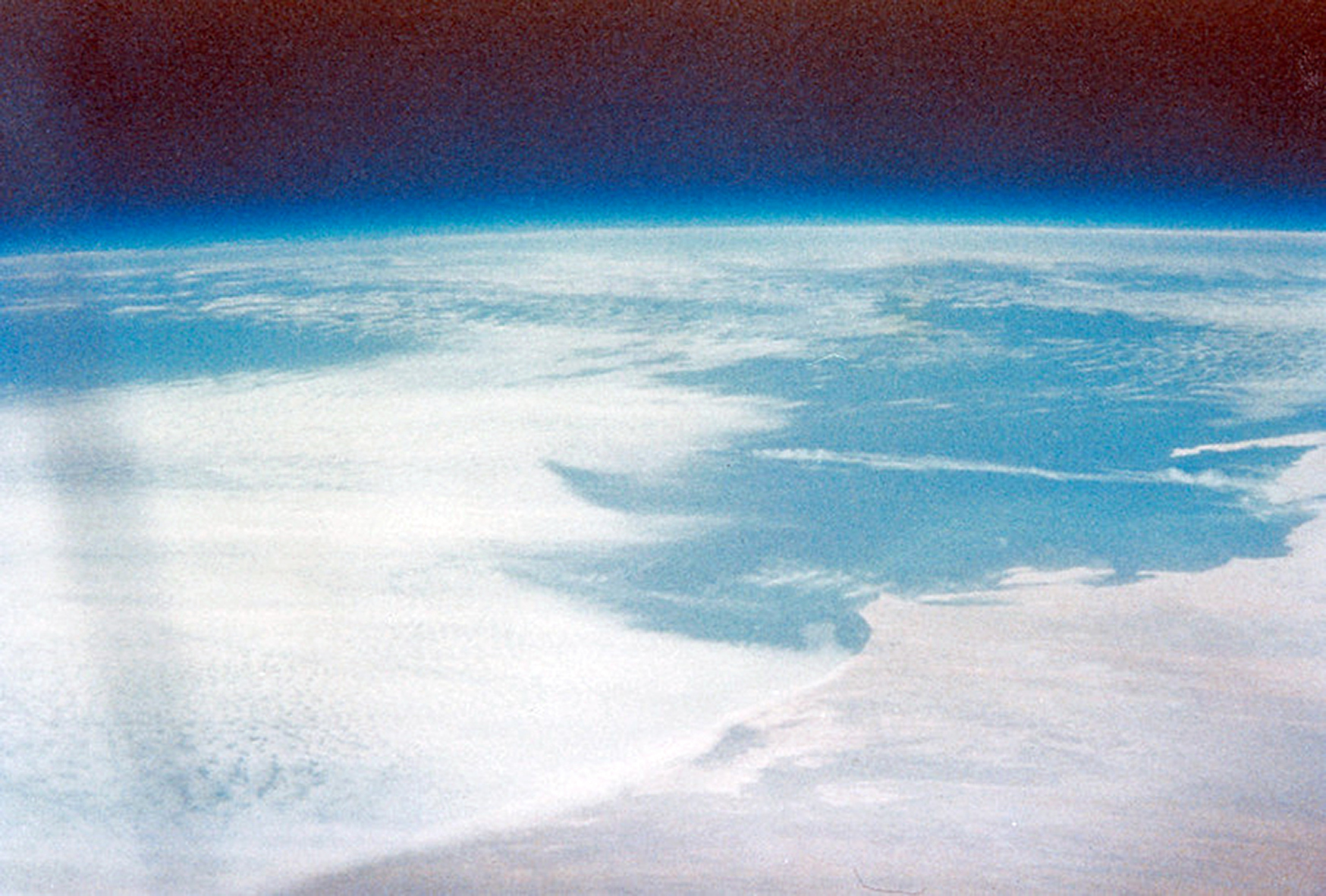

Carpenter was impressed with both the view out of the window and the fact that the only evidence of his tremendous orbital speed was from the readings on his instruments. All seemed fine during the initial check of the displays, but it would be some time before it was realised that the Pitch Horizon Scanner (PHS) was optically sensing his spacecraft's pitch with an error of 20 degrees. After viewing the spent Atlas, Carpenter reported that he was dropping behind time because of difficulty in loading his camera with the special film required to film the Earth-horizon limb. He was also becoming increasingly warm in his suit.

He found that using the periscope on the dark side of the Earth was ineffective and was unsure of his exact attitude until the daylight pass, when a landmark gave him the required reference point. He was surprised by how much of the Earth was covered by clouds. The illumination from the on-board clock also hampered his view of the stars, while the cloud cover over Woomera, Australia obscured his view of the ground flares. These were set to burn for 90 seconds and were ignited at 60-second intervals. Flare ignitions on the other two passes were subsequently abandoned because the cloud cover had not lifted.

Carpenter evaluated bite-sized food pieces on his flight, as opposed to the squeeze-tube, baby-food-type used by Glenn. He reported that they were tasty and good to eat, although there was the added problem of eating with gloved hands and bypassing the helmet microphones. He commented that the crumbs, while not an immediate problem, might hamper future space voyages and could potentially be dangerous to breathing.

During the first and second orbits, Carpenter conducted frequent capsule manoeuvres, evaluating both the fly-by-wire and manual propulsion systems to observe and photograph Earth phenomena and support other experiments. He pointed the capsule 'up' towards space and 'down' towards the Earth, experiencing difficulty in re-setting the gyros and having to recycle them after they tumbled outside their limits on two occasions. He had a busy manoeuvring and experiment programme in order to expand upon the data and experience gathered during Glenn's flight. It would prove to be a challenge and a problem for the outcome of the flight.

As the flight continued, the Mylar plastic aluminised balloon was released as the spacecraft passed over the Cape to start the second orbit. It was planned that the balloon would deploy to 50 cm (20 in) diameter at the end of a 30-metre (100-foot) tether. Any drag on the balloon would be recorded through the anchoring arm. The balloon consisted of five panels of orange, silver, white, yellow and phosphorescent (for night-side observations), with the colours chosen to determine which would be the most visually reflective under varying conditions of illumination. This experiment would have direct application for future experiments in developing rendezvous and docking targets for the Gemini and Apolo programmes, where accurate identification of targets in both day and night passes would be important as two spacecraft closed in on each other for physical contact.

Carpenter reported that the balloon had only partially inflated, but noted that the most reflective panels in sunlight were the orange and silver sections. There was no effect from the drag of the balloon on the spacecraft, while at times the tether was taut and at other times it was slack. A number of multi-coloured 5 cm (2 in)-diameter Mylar discs were deployed from the folds of the balloon, to provide a man-made reference and comparison with luminous particles. These were first reported by Glenn and confirmed by Carpenter and were later determined to be ice particles originating from the sides of the spacecraft. The plan was to separate the balloon at the end of the experiment, but it refused to release and stayed with the capsule until re-entry.

The other experiment related to the Gemini programme was the observation of liquids in both a weightless state and under the G-forces of entry, to determine the behaviour of liquids in varying G loads. This would help in the design of spacecraft storage tanks and re-startable engine systems. Inside the cabin was a 75 mm (3 in)-diameter flask with a central standpipe that had three holes in its base. These holes provided passage for the liquid into the pipe, allowing the liquid to move by surface tension rather than just floating around as globules. The liquid mixture was a combination of distilled water, an aerosol solution that reduced surface tension, a silicone additive and a green dye to aid photography.

The combination of manoeuvring the spacecraft to perform observations and engineering tasks, as well as completing his experiments and inadvertently activating the very sensitive attitude control jets (thus initiating "double authority control" where both the automatic and manual systems were activated) resulted in 42% of manual attitude control supply reserves and 45% of that in the automatic tanks being used by the end of the second orbit. By the time the third and final orbit began, the fuel supply was less than 50%. With the mission requirement to conserve fuel to leave enough for the re-entry orientation and operations, Carpenter had to let Aurora 7 free-drift for almost a complete orbit. Although this was a necessity due to the fuel situation, the official NASA history later tried to turn this into a positive, reporting that, "This vehicle control relaxation maneuver, if successful, would be a valuable engineering experiment. The results would be most useful in planning the rest and sleep period for an astronaut on a longer Mercury mission." Aboard the spacecraft, meanwhile, Carpenter was enjoying the free-drift mode, taking more iimages of the Earth and Moon and observing various atmospheric phenomena.

Entry and Landing

Observations from his spacecraft had occupied the astronaut so fully that when Hawaii instructed Carpenter to begin his retro-fire, he informed them that he was running behind schedule in the checklist. As he used the automatic stabilisation system, he found that it would not hold the spacecraft in the correct attitude. In trying to determine what was wrong, he fell further behind the checklist and when he quickly switched to the fly-by-wire system he forgot to switch off the manual one, allowing both to consume more precious fuel for the next ten minutes.

Eventually, Carpenter aligned the spacecraft. Because the automatic system was playing up, he initiated a manual retro-fire - but a few seconds later than planned. This resulted in a 25° error to the right, which would lead to a 282-km (175-mile) overshoot of the planned landing area. Firing the retros three seconds late added a further 24 km (15 miles) to that figure and a below-nominal performance of the retros pushed the overshoot by another 96 km (60 miles). It was later determined that if he had not overridden the automatic system, Carpenter could have overshot his landing target by a far greater distance than he actually did.

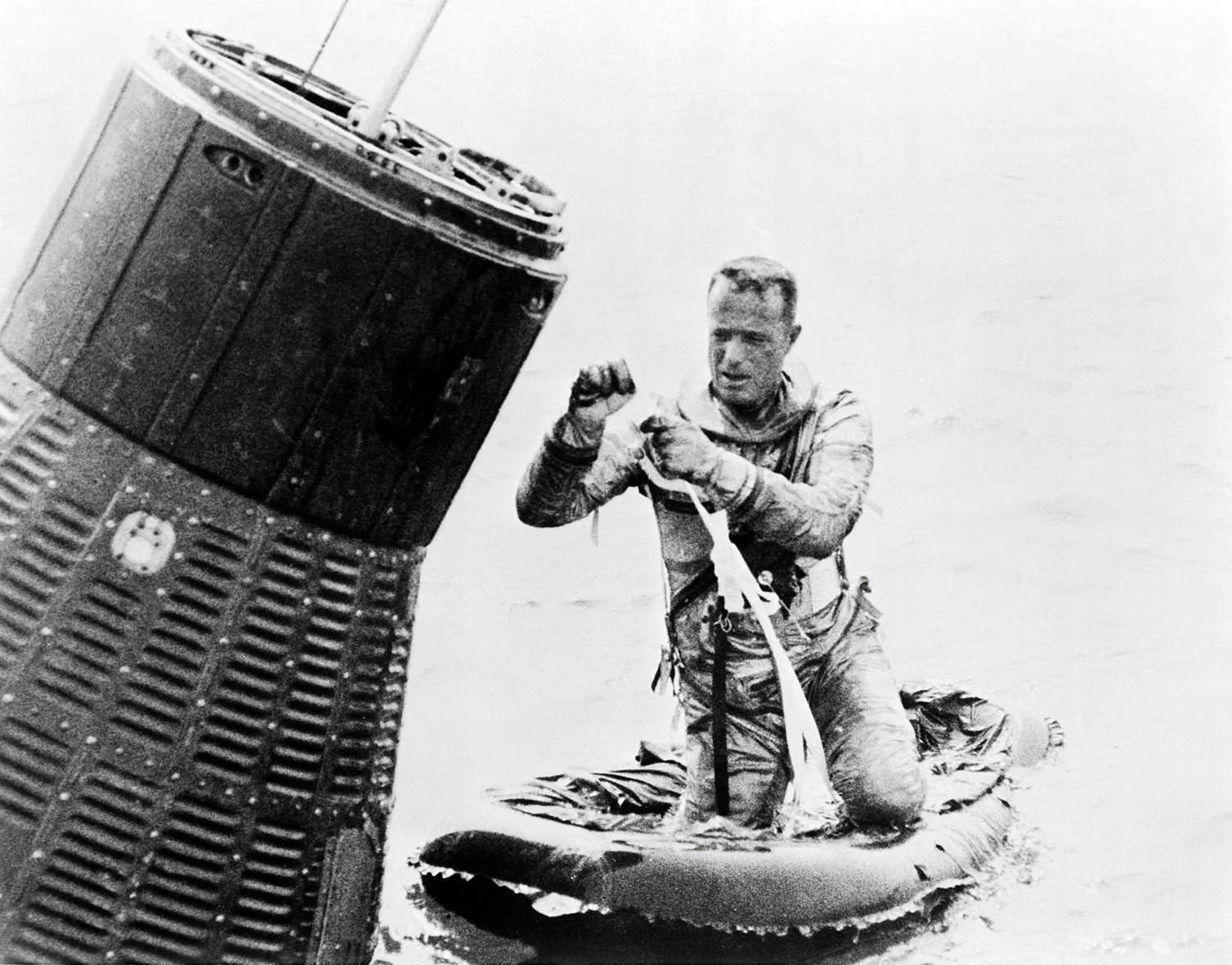

The actual descent and landing was uneventful, with Carpenter describing the splashdown as noisy but less of a jolt than he expected. He landed in the Atlantic Ocean, 200 km (125 miles) north-east of Puerto Rico after a three-orbit flight lasting 4 hours 56 minutes and 5 seconds. Carpenter had been told over the radio that it would be an hour before the recovery divers could reach him. Realising he had overshot and unable to raise a reply to his radio messages, he decided to evacuate his capsule. Mindful of Grissom's hatch incident with Liberty Bell 7 (Mercury-Redstone 4 in July 1961), Carpenter checked the position of his craft in the water and found that it was lying deeper than would be safe for a nominal side hatch exit. With effort, he squeezed out of the neck exit at the top of the spacecraft. This tight squeeze in his suit caused him to sweat profusely in the 101° temperature inside the spacecraft. With considerable effort, he safely deployed and entered his life raft, carrying his flight camera.

While Carpenter was struggling out of the spacecraft and was out of communication range, the rest of the world knew he was down but not whether he was alive. A full-scale aerial search of the landing area and surrounding ocean was conducted, looking for and eventually finding signal beacons from the spacecraft. About 36 minutes after his landing, the first aircraft approached and pinpointed the downed astronaut for the rest of the search team. An hour after landing, the first pararescue divers arrived to help him. Carpenter looked happy and relaxed and not at all tired. Three hours after hitting the water, he was hoisted aboard a helicopter for a one-hour flight back to the recovery ship.

Post-flight debriefing began aboard the carrier USS Intrepid and was followed in the ensuing days and weeks by the celebrations and awards that had been initiated by Glenn's flight, though on a slightly smaller scale. On the whole, the mission was termed a success and enabled planning for an extended six-orbit mission to go ahead for the next flight later that year. Carpenter insisted in the post-flight debriefings that he knew what he had to do at all times in the flight, but that it took longer than planned to do it all. He expressed concern over the lack of long-term preparation available for training on the flight plan, not alluding specifically to replacing Slayton at short notice, but suggesting that at least two months should be allowed for the flight astronaut to practice the flight plan. He assumed full responsibility for excessive use of the onboard fuel.

The controversy over MA-7 copntinued for years after the flight. Just as speculation over Grissom's denial of blowing the hatch of Liberty Bell 7 would not go away, the activities of Carpenter also raised doubts even 30 years after the mission, when Flight Director Chris Kraft wrote in his biography in 2001 that he was not happy with the astronaut's performance. Carpenter addressed this in his own biography in 2003.

The official NASA history indicated that Kraft was pretty happy with Carpenter and the mission up to the point of entry, but Kraft indicated that he was determined that Carpenter should never fly again while he remained at NASA. In the event, MA-7 did turn out to be Carpenter's only flight, the operation of the mission being only part of the reason why he never returned to space. A motorcycle injury and a growing interest in underwater exploration meant that he had returned to the Navy full time by 1967, having spent 30 days underwater in Sealab II in 1965. The second American in orbit might not have been able to make a return to orbit, but he could certainly claim to be the first to have lived in both outer and inner space.