Astro Info Service Limited

Information Research Publications Presentations

on the Human Exploration of Space

Established 1982

Incorporation 2003

Company No.4865911

E & OE

Gemini 4

GEMINI 4 MISSION REPORT |

LAUNCH DATA |

|

|

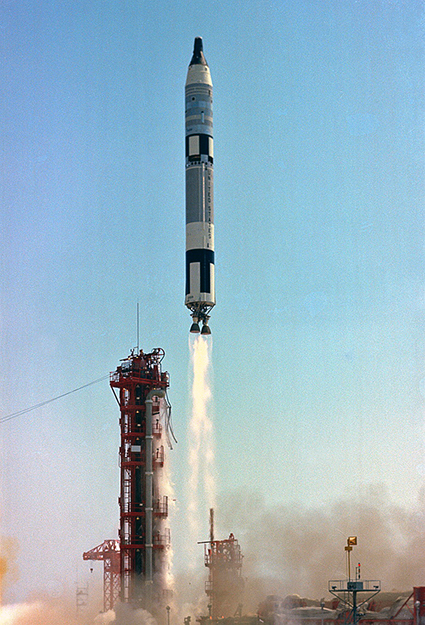

Launch |

3 June 1965. 10:15:59 EST |

Launch Site |

Pad 19, Cape Kennedy, Florida, USA |

Launch Vehicle |

Titan II Gemini Launch Vehicle No. 4 (GLV-4) |

Spacecraft |

Spacecraft No. 4 |

Spacecraft Mass |

Approx 3,574 kg (7,879 lbs) |

|

|

MISSION OBJECTIVE |

Four-day extended mission duration; evaluation of work procedures, schedules and planning for extended duration missions; first US spacewalk (EVA); spacecraft manoeuvres. |

|

|

CREW DATA |

Crew Position |

Name |

Mission |

Command Pilot |

James A 'Jim' McDIVITT, 35

USAF |

1st |

Pilot |

Edward H. 'Ed' WHITE II, 34

USAF |

1st |

|

|

Flight Crew |

2 |

Call Sign |

Gemini Four |

Back-up Crew |

Frank Borman (Command Pilot)

James A. 'Jim' Lovell Jr. (Pilot) |

EVAs |

1 (One planned) |

|

|

MISSION DATA |

Flight Duration |

4 days 1 hour 56 minutes 12 seconds |

Distance Travelled |

Approx 2,590,600 km (1.609.700 miles), completing 66 orbits |

Orbital Data |

165.8 x 293.7 km (103 x 182.5 miles), with a period of 88.94 minutes |

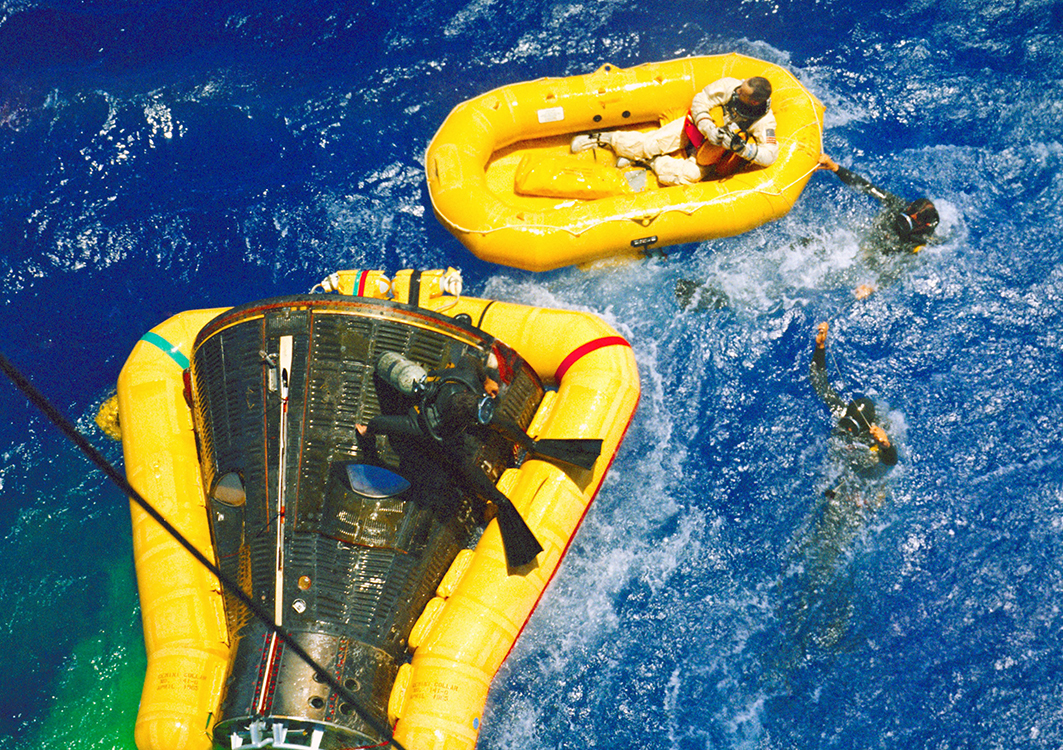

Landing |

7 June 1965. 12:12:11 EST |

Landing Site |

Western Atlantic Ocean; prime recovery ship USS Wasp. |

|

|

Extending the Duration

By the summer of 1965 only one American astronaut had spent more than a day in space, compared to four Soviet cosmonauts. With Apollo lunar flights planned to last between one and two weeks, NASA had to start exploring the challenge of longer duration space flight in order to understand the medical hurdles and address the effects of endurance missions on equipment and systems. Therefore, across just six months in 1965, three Gemini missions (starting with Gemini 4) would gradually increase mission duration to four, then eight and ultimately 14 days.

In addition to the four-day duration, the crew of Gemini 4 - astronauts Jim McDivitt and Ed White - were to attempt to rendezvous on their first orbit with the spent second stage of their Titan launch vehicle. Then, on the second orbit, White would attempt America's first EVA (Extra-Vehicular Activity, or spacewalk), perhaps even journeying across to the spent stage by means of a hand-held jet manoeuvring gun. For the rest of their mission, the pair would alternate sleep periods to allow at least one of them to monitor the spacecraft's systems and perform a suite of scientific experiments. The plan looked achievable on paper, but the reality once on orbit became very different.

The two astronauts chosen to fly Gemini 4 were first-time fliers from NASA's Group 2 selection named in September 1962. McDivitt and White were also firm friends, having attended and graduated from the University of Michigan together in 1959 and as members of the same class at the USAF Test Pilot School (Class 59-C). Their friendship and ability to get on with each other were leading factors in their selection to fly the demanding Gemini 4 mission.

Beaten by the Soviets

The origins of an astronaut conducting an EVA from Gemini can be traced back to March 1961, when NASA proposed short, one-man spacewalks from what was then Mercury Mark II (which became known as Gemini from the following year). As the Gemini concept developed over the next four years, the initial target for Gemini 4 was merely to have an astronaut just standing up on his seat in the open hatch of the spacecraft on orbit. The full EVA was targeted for the third crewed mission, Gemini 5. There were also studies for a full EVA on Gemini 4 before the Soviets could achieve the feat and a simulated hatch opening by the Gemini 3 crew in an altitude chamber in November 1964 helped to move this idea forward.

However, on 18 March 1965, the Soviets scored another 'space first' when cosmonaut Alexei Leonov left the Voskhod 2 spacecraft for about ten minutes and became the first person to walk in space. In the aftermath of Leonov's achievement, the pace for a full-exit EVA on Gemini 4 stepped up in secret, with the programme of preparations and training for the spacewalk completed under strict security over several weeks under the less-than-imaginative code name of 'Plan X'. The decision to go for the full EVA was made on 25 May 1965, only nine days before the planned launch.

Rendezvous with Titan

Six minutes after launch, Gemini 4 was in orbit and separated from the Titan second stage. Almost immediately, McDivitt turned the spacecraft around as White busied himself with post-insertion checklists, while lamenting not having a camera handy to photograph the booster glinting in front of them. McDivitt immediatey noticed that the stage was tumbling slowly and, over the next orbit, they expended a lot of fuel in trying both to rendezvous with the stage and even just keep in touch with it as it moved away from them. McDivitt became the first astronaut to experience the difficulty of space rendezvous as he tried to fly his spacecraft directly at the target stage instead of dropping below it in into a shorter, but ultimately faster, lower orbit. Frustrated at not being able to reduce the distance between the spacecraft and the stage, while seeing the tumbling rate increase, McDivitt advised Mission Control that they were using up too much fuel (about 25 percent) in trying to keep in touch with the booster and suggested abandoning any further attempts in order to conserve the remaining fuel, to which Mission Control concurred.

Floating Free

With the difficulty of staying in touch with the Titan II stage, all thoughts of White spacewalking over to it were abandoned. As soon as the rendezvous exercise was over, the focus for the crew shifted towards preparations for the EVA. Both astronauts were dressed in their pressure suits, with White's specially manufactured for protection in the hazardous environment outside the spacecraft. Another unexpected hurdle encountered was in preparing and attaching other equipment, such as the umbilical and tether, in the tight confines of the Gemini capsule, which White found tiring and challenging. With the crew finding it difficult to keep to the timeline to allow White to open the hatch on the second orbit, McDivitt requested - and was granted - a one-orbit delay to allow them to catch up and rest before attempting the EVA.

Some 90 minutes later, now rested and fully kitted out, Ed White was ready for the EVA, only to encounter some difficulty in opening the hatch. Fortunately, the astronauts' attention to detail during their training paid off, as McDivitt had studied the latching mechanism very closely and knew where the problem lay. He told White to release the latch in the mechanism manually and free a troublesome spring, which he did successfully. Though the hatch "popped open", it still required some force to push it to the fully open position. White now stood on the seat to attach a camera to the outside of the spacecraft before finally pushing off gently, using the force of the Hand-Held Self-Maneuvering Unit (HHSMU, or jet-gun) to propel himself into space. His distance would be limited by the 25m (82 ft) tether and life-preserving umbilical which was supplying the oxygen to his suit.

With no specific tasks to accomplish other than evaluating the hand-held gun and the dynamics of the tether, White tumbled outside for 20 minutes. McDivitt was occupied by keeping the spacecraft steady, ensuring that the manoeuvring jets fired away from White and photographing his colleague outside. White used a camera mounted on the manoeuvring unit and though he managed to take a few images, most were found to be grainy and unsuitable. Those taken by McDivitt, however, became some of the most iconic images of the American space programme.

After the fuel ran out in the HHSMU, White found it more difficult to control his attitude, although by pulling on the tether he found that he could literally 'stand' on the outer skin of the spacecraft. He deliberately stayed clear of the back of the spacecraft, which was out of McDivitt's line of sight. He also kept clear of the thruster firings, but did inadvertently brush up against McDivitt's window, smearing it and earning a friendly rebuttal. With communication difficulties, the enthusiastic and exuberant White was having so much fun outside that neither astronaut heard the calls from Mission Control for him to end the EVA and return to his seat inside the capsule. When he did, White exclaimed that it was "the worst moment of his life". Standing in the hatch again, trying to squeeze back inside and close the hatch proved as difficult as it had been getting out, taking much longer than they had expected. Eventually, the hatch was closed and sealed.

Day by Day, Orbit by Orbit

The crew could now settle down to fulfil the four-day challenge, though manoeuvring Gemini was now limited due to the excessive use of fuel trying to stay with the Titan stage. As a reslut, they spent long periods of the remaining flight in free drift. They had 11 experiments to conduct, however, including ground, atmosphere and weather photography, studies of radiation levels inside and outside the spacecraft, navigation studies and medical investigations. One experiment examined the levels of static electricity on the spacecraft, which had application for potential problems on future docking missions. As this was the first opportunity to extend American duration in space, the medical experiments carried a high priority. One of these was a bungee cord stretched between the hands and feet for exercise.

An understated aspect of Gemini 4 was learning to live in space for four days. Known as 'habitability', these studies required evaluation and feedback on the basics, such as eating, drinking, sleeping, work patterns and toilet requirements. Not the most glamorous aspect of being an astronaut, but it had far-reaching application for longer flights and 'routine' operations in space.

During the mission, McDivitt reported that he had sighted two mysterious objects in orbit. Initially thought to be satellites, erroneous vision due to dirty windows, or other space debris, there was a lot of media speculation - and cartoons - about what they might have been. Unsurprisingly, UFO stories abounded as well, but to this day there has been no official confirmation of what the astronaut saw or what it might have been.

Meeting with a Cosmonaut

After surpassing the American space endurance record, Gemini 4 returned to Earth on 7 June. A planned lifting re-entry was rendered impossible when the onboard computer failed during the latter stages of the mission. This resulted in a ballistic re-entry instead. Following a successful splashdown, NASA now had renewed confidence for both the longer Gemini missions and for planning the Apollo lunar flights. After the flight, the Gemini 4 crew enjoyed a popular period of post-flight celebrations, both at home and abroad. This included attending the 1965 Paris Air Show, where they met Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin.

After Gemini 4

Ed White remained in the Gemini programme for a short while, serving as back-up Command Pilot for Gemini 7 before being assigned as Senior Pilot on the first Apollo crew (Apollo 1). Tragically, White and his colleagues, Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee, were killed on 27 January 1967 in the Apollo 1 fire on Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy. Had he lived, it was very likely that White would have had an illustrious astronaut career, perhaps including walking on the Moon.

Following his Gemini 4 duties and a stint as Capcom for Gemini 5, Jim McDivitt was reassigned as Apollo Branch Chief in the Astronaut Office. In the spring of 1966, he was chosen to comand the first crewed test of the Lunar Module in Earth orbit. Changes in the flight manifest, the aftermath of the Apollo 1 fire and delays in preparing the Lunar Module for flight meant that McDivitt and his crew would be training for three years before finally flying the mission as Apollo 9 in March 1969. From September 1969 until June 1972, McDivitt served as the Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager, before finally leaving NASA to pursue a career in business until his retirement in 1995.

This mission report is copyright Astro Info Service Ltd 2018, 2025.

All images are courtesy of NASA, unless otherwise stated.

The mission emblem for Gemini 4.

The Gemini 4 prime crew of Pilot Ed White (left) and Command Pilot Jim McDivitt.

The food packages that would be evaluated on Gemini 4 included beef and gravy, peaches, strawberry cereal cubes and beef sandwiches. The water gun shown at the top would be used to reconstitute the dehydrated food packages.

Carrying their portable air conditioners, McDivitt (front) and White walk up the ramp at Pad 19 on their way to board the Gemini 4 spacecraft prior to launch.

Gemini 4 blasts off from the launch pad at 10:15 EST on 3 June 1965.

An iconic image and a historic moment as Ed White performs the first American spacewalk, on the third orbit of Gemini 4 on 3 June 1965. White's spacesuit was specially manufactured to protect him in the hazardous environment outside the spacecraft, including the gold plating on his helmet visor.

This second image more clearly shows the important equipment used by White on the EVA, including the gold-plated visor and the 25m umbilical tether and oxygen supply wrapped in gold tape to keep them together. In his right hand is the Hand-Held Self-Maneuvering Unit (HHSMU), or 'jet-gun', which White used to control his movements in space until its fuel was depleted.

An on-board shot of Ed White on Gemini 4, which would turn out to be his only space flight. Tragically, he was killed in the Apollo 1 pad fire on 27 January 1967, together with his colleagues Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee.

A team of US Navy frogmen participate in the recovery of the Gemini 4 crew after splashdown on 7 June 1965. One of the crew is already in the life raft awaiting the recovery helicopter, while the capsule is kept afloat with buoyancy aids.

During their post-flight tour, the Gemini 4 crew attended the 1965 Paris Air Show, where they met up with the first man in space. Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin is bottom left of the picture, shaking hands with Ed White (centre-right facing the camera) and Jim McDivitt (bottom right)

For the in-depth story of the mission, see David Shayler's 2018 Springer-Praxis title

GEMINI 4.

Further details can be found in our SHOP