Astro Info Service Limited

Information Research Publications Presentations

on the Human Exploration of Space

Established 1982

Incorporation 2003

Company No.4865911

E & OE

Expedition Zero Pt 7

Expedition Zero ISS Operations

Part Seven - Setting The Stage

August 2000: Preparing for Shuttle Flights to Resume

At the start of August, with Zvezda securely linked to Zarya and Unity, the core of the International Space Station was finally taking shape. The next phase would entail completing the necessary requirements to sustain a crew aboard for several months without the limited-duration support of a docked Shuttle orbiter. This would be a key step forward in the complex, step-by-step construction and outfitting assembly schedule that was planned for the next few years - barring any unforeseen delays or setbacks. Taking recent events into consideration, the ISS partners agreed to update the launch schedule for the outstanding elements in the assembly sequence. The first phase of orbital assembly through to the end of 2001 would remain unchanged, but subsequent missions were prioritised, with the station assembly flights expected to be completed by April 2006 according to the sixth (Revision F) assembly planning document.

Prior to the hand-over of computer control between Zarya and Zvezda, the Service Module's three computers were re-booted to ensure they were correctly synchronised. With Zvezda's own Motion Control System (MCS) now handling the attitude control manoeuvres of the 55,000-kg (60-ton) complex, the early communications system on the US Unity node was also transferred to the computer system on the Service Module. On-board equipment could now be powered via ground commands from the Russian Mission Control in Moscow, through the NASA MCC in Houston and on up to ISS. For this early phase of ISS assembly, a network of Russian ground stations was the primary link for sending commands to and receiving data from the space station. Other tasks completed prior to the arrival of the first automated Progress re-supply craft included a programme of routine battery cycling on Zarya and a test of its Kurs ("Course") automated docking system.

Making Progress

On 6 August, the first Progress re-supply spacecraft, M1-3 (serial No. 251), was launched on a Soyuz U from Area 1 at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. This spacecraft was the latest uncrewed version of the venerable Soyuz spacecraft, first introduced in 1978 to re-supply crews on Salyut 6. Regularly upgraded, the series continued with frequent supply missions to the Salyut 7 and Mir stations prior to beginning ISS cargo support requirements after the arrival of Zvezda. What was confusing was that NASA termed the vehicle as Progress 1 (or administratively as ISS-1P), which it was not. It was actually the 88th flight in the series, though of course it was the first to the new station. That administrative labelling continues with both Progress (*P) and Soyuz (*S) flights to this day.

Stocking Up for Expedition One

Progress M1-3 took two days and completed three rendezvous burns to reach the ISS, docking at the rear port of Zvezda late on 8 August [all times are UT]. The final approach and docking took place in orbital darkness, but a floodlight on Progress illuminated the Zvezda docking port and the first TV orbital views of the module since its docking with Zarya. The Progress carried 2,434.2 kg (5,366.49 lbs) of cargo, including 1,559.4 kg (3,437.88 lbs) of fuel for the attitude control motors. There was also 615 kg (1,355.84 lbs) of dry cargo to continue outfitting the module's systems to support human occupation, the Elektron ("Electron") oxygen regeneration system, the Vozhdukh ("Air") carbon dioxide removal system, computers and various other consumables.

A Russian press statement, issued to coincide with the docking, suitably noted the achievement but also the dilemma that the leading Russian hardware provider was facing at that time from its own government and state agency. With the docking of Progress M1-3, the Energia Corporation had fulfilled its obligations to the value of one billion roubles (approx $36 million US in 2000), a significant amount that was yet to be reimbursed by the Russian Ministry of Finance and Roscosmos. The delay in settling the account threatened the continued participation of Russia in the programme and the manufacture of other Russian modules, as well as the Soyuz and Progress transport and logistics vehicles required to meet the obligations to the other 15 partners (at that time) of the ISS programme.

Unloading the Progress would be a primary task for the crew of STS-106 (ISS assembly flight 2A.2b), which was scheduled to arrive the following month. Up on orbit, regular leak checks were being made on the pressurised areas between Progress and Zvezda to ensure there were no seepages. With Progress docked in line to Zvezda, Zarya and Unity, the core of the station now stretched to 43.58 metres (143 feet) in length and had a mass of over 60,000 kg (67 tons). Using a camera on the exterior of the Zarya module, confirmation was received that one docking target on Zvezda had only partially deployed. Though this would have no immediate impact on operations, NASA investigated the possibility of a manual deployment by two of the STS-106 crew during their scheduled EVA.

After checking the propellant lines between Progress and Zvezda, the command to begin propellant transfer to the Service Module was issued on 10 August. The fuel transfer was successful, even though the the attitude control thrusters on Zvezda were shut down for approximately 2.5 hours during the operation due to a ground command error. Fortunately, no serious damage was done as ISS was in a stable orientation requiring only a few thruster firings. Subsequent commands established full operation of the atitude control system once again. However, during the following day's transfer of oxidiser, an installation issue caused the operation to shut down automatically. On 15 August, a test firing of the Progress M1-3 thrusters slightly increased the velocity of the station by 1 m/sec (2 mph). Another firing a couple of days later changed the velocity again by 4 m/sec (9 mph). Over the next few weeks leading up to the arrival of STS-106, one or two further firings could be needed to fine-tune the pitch for the Shuttle rendezvous.

While the proceedings remained tense, contollers in the US and Russia noted irregularities in the charging and discharging of one of the five batteries aboard Zvezda. With the other four operating perfectly normally, a single battery problem was not an immediate issue and while the problem was undergoing troubleshooting, three additional batteries were on standby for the STS-106 mission.

By the end of August, propellant transfer from the tanks aboard the Progress to those on Zvezda had been completed. In addition, tests of the efficiency of the solar arrays showed that everything was in good condition. Although there were ongoing issues with the suspect battery, this had no serious impact on station operations.

September-October 2000: The Space Shuttle Returns to ISS

Early September 2000 saw the next Shuttle mission fly to the newly expanded station. STS-106 (Atlantis, 8-20 Sep) would resume preparations for the arrival of the first resident crew a few weeks later. There remained significant work to be completed before the station could support a resident crew without a Shuttle docked at the same time, so the next couple of months would be critical in turning the unoccupied modules into a fully operational space station.

Crew of STS-106

Terence W. Wilcutt, NASA, CDR, 4th flight

Scott D. Altman, NASA, PLT, 2nd flight

Edward T. Lu, NASA, MS-1, 2nd flight

Richard A. Mastracchio, NASA, MS-2/FE, 1st flight

Daniel C. Burbank, NASA, MS-3, 1st flight

Yuri I. Malenchenko, Roscosmos, MS-4, 2nd flight

Boris V. Morukov, Roscosmos, MS-5, 1st flight.

STS-106 was officially the second half of one mission from the original manifest. The delay in the launch of Zvezda led to the original STS-101 mission (ISS 2A.2 Atlantis) being split into two flights: STS-101/2A.2a flown prior to the arrival of Zvezda and a new mission, STS-106/2A.2b, continuing the work required once Zvezda was permanently attached to Zarya and the first uncrewed Progress re-supply craft had been docked to the Service Module. The only EVA of STS-106, on 11 September, saw the astronauts (Lu and Malenchenko) manually deploy the docking alignment target to its maximum extent. The EVA crew also deployed the CM-8M magnetometer as a back-up sensor for the station's attitude control system and mounted a Russian Yakor ("Anchor") foot retraction near the magnetometer. The 6-hour 14-minute EVA also included connecting cables between the two Russian modules.

Multi-role Crewmembers

For a week at the station, in addition to conducting the EVA, the STS-106 crew became a multi-tasking team inside the new module as they moved over 2,994 kg (6,600 lbs) of logistics and hardware, clamped the module and tackled plumbing, electrical and installation tasks. The crew focused on unloading the Progress M1-3 cargo craft and removed the Zarya tele-operated control subsystem and the docking mechanism probe between the two Russian modules as they were now permanently coupled. Inside Zvezda, they installed additional computers, a velo-ergometer static exercise bike, a treadmill, th Elektron oxygen generation system, a toilet, batteries, amateur "Ham" radio systems and other equipment. A systems test to evaluate the quality of downlink communications from Zvezda's Rassvet ("First Light") telegraph-telephone-based system was also completed. This would be the primary communications system until the full system could be installed by a later Shuttle mission.

No Time to Spare

As September drew to a close, the workforce at KSC in Florida was preparing for the next Shuttle mission, STS-92 (ISS-3A Discovery). This would be the final Shuttle assembly flight before the EO-1 crew arrived in early November. It would deliver the first element of the station's backbone assembly, the Z-1 Zenith Truss, as well as the third Pressurised Mating Adapter (PMA-3). It was a busy time at the Cape, ensuring the final pieces were in place prior to dispatching the first resident crew to the station.

In the meantime, ground flight controllers resumed recycling the multi-purpose battery system on the now unoccupied station, to maintain its health prior to Discovery's arrival.

One Hundred Up

Two days into its STS-92 mission (the 100th flight of the Shuttle programme) and 17 months after its first visit in May 1999, Discovery returned to the station on 13 October 2000, docking at the PMA-2 forward port on Unity. The crew opened the hatches to access the station less than three hours later.

Crew of STS-92

Brian Duffy, NASA, CDR, 4th flight

Pamela A. Melroy, NASA, PLT, 1st flight

Leroy Chiao, NASA, MS-1, 3rd flight

William S. McArthur Jr., NASA, MS-2/FE, 3rd flight

Peter J. K. Wisoff, NASA, MS-3, 4th flight

Michael E. Lopez-Alegria, NASA, MS-4, 2nd flight

Koichi Wakata, NASDA (now JAXA), MS-5, 2nd flight.

The primary objectives of this fifth Shuttle ISS mission (designated as assembly mission 3A) were the transfer and installation of the Z-1 Truss and PMA-3. Though Discovery remained docked to the station for over 165 hours, the crew spent only just over a day inside the ISS due to the heavy EVA programme in the flight plan.

The operation to move the Z-1 Truss from Discovery's payload bay took place on Flight Day 4 (FD4), 14 October, with the Shuttle's Remote Manipulator System (RMS) being used to lift the 8,755 kg (19,300+ lbs), 4.8-m-long and 4.2-m-diameter (15 ft 8 in x 13 ft 9 in) element into place on the uppermost (zenith) docking port of the Unity module. It was not a straightforward procedure, as a short-circuit in Discovery's electrical system affected the Space Vision System (SVS) that provided computerised alignment information for the RMS and the payload. An upward-looking keel camera tracked the movement of the huge structure as it slowly left the payload bay. Between the crew and Mission Control, a back-up plan was created to solve the problem, 2 hours and 15 minutes behind schedule, using back-up equipment and an alternative power source. All systems apart from the keel camera were restored, with the Z-1 now firmly attached to the Unity module.

The following day, the first of four consecutive EVAs, by two alternating pairs of astronauts, got underway. The tasks for the four spacewalks included connecting umbilicals between the new truss and Unity and moving PMA-3 from the Shuttle's payload bay to the vacant port directly opposite the Z-1 Truss (the nadir, or lower port) on Unity. The EVA crews also relocated communications equipment and EVA tool stowage boxes, installed AC-to-DC electrical converters and performed several other get-ahead tasks. A test flight was conducted on the SAFER (Simplified Air For EVA Rescue) small backpack, intended to be used as a regular backpack system on future EVAs. Together, the four STS-92 EVAs totalled over 27 hours.

With the spacewalking activites over, the Shuttle crew then focused on work inside the station, completing internal connections to the Z-1 Truss and transferring equipment and supplies in preparation for the first resident crew's pending arrival. The Discovery crew also tested the four 286 kg (630.5 lbs) Control Moment Gyros (CMGs) housed in the Z-1 Truss. These would be used to orientate the station. During the test, they gyros were spun up to 1,000 rpm to confirm their design parameters for speed and power. They would become fully operational in the new year, spinning at 6,000 rpm. The CMG heaters were also tested, to ensure they protected the gyros from the intense cold of space. The crew collected microbial swabs from surfaces around the station, to identify any growth and then mitigate it by wiping down surfaces with fungicide.

Preparing for New Residents

Discovery departed the ISS on 20 October (FD 10) and landed safely four days later. Five days after the end of the STS-92 mission, a dress rehearsal of the planned Expedition 1 docking procedure was conducted with the unoccupied station to test all ISS commands.

On 29 October, with the Z-1 Truss pointing outwards towards the Sun to maintain the required temperatures while awaiting the arrival of the first crew, the station was moved to duplicate what would be done in the actual docking, as NASA reported: "The station was commanded to orient itself to be horizontal to the surface of the Earth, perpendicular to its direction of travel, with the Zvezda module pointing southward, the Unity module pointing northward and the newly-installed Pressurised Mating Adapter 3 pointing 'up' towards the Sun." In the days prior to the arrival of the resident crew, the final propellants were transferred from Progress M1-3 to Zarya's fuel storage tanks.

Generally, all the new systems on the ISS were working as designed, but NASA did note that one of the three flight control computers on Zvezda had been "automatically taken offline". This was a normal procedure, as the three computers could "vote" one offline upon detection of a data difference. To overcome this required a re-boot of the computers. Further analysis was conducted on the software on the third computer, to determine whether there was an operational problem with the software or the hardware and when it might be safe to bring it back online. If necessary, the ISS could operate safely on just one computer, but having one or two more online would provide additional redundancy.

With the conclusion of the docking procedure rehearsal, the stage was set for the first resident crew to arrive just nine days later, beginning a remarkable era in the story of human space flight.

EXPEDITION ZERO - A SUMMARY

The "Expedition Zero" pre-resident crew period lasted just under two years, from the launch of the Zarya Control Module on 20 November 1998 until the Kurs system on Soyuz TM-31 guided the spacecraft into the aft docking port of Zvezda on 2 November 2000, thereby signalling the arrival and formal start of ISS Expedition 1.

By the Numbers

During these first 23 months of station orbital operations, the Russian Zarya and Zvezda modules launched and connected to create the early core of the station. This period saw the arrival of five Shuttle assembly and logistics missions and one Progress re-supply vehicle. The first Shuttle flight, STS-88, began the assembly of the US segment by adding the US Node 1 "Unity", providing what was planned as a permanent attachment to the Russian segment (Zarya and Zvezda). STS-96, 101 and 106 were primarily logistics missions to stock up the station with supplies and spares in support of the early resident crews, while STS-92 added the Z-1 Truss from which the remaining elements of the station's enormous truss backbone would be constructed and enable solar arrays to be added by later Shuttle missions.

In total, the five Shuttle missions docked at the station for a total of just over 33 days, with the hatches to the station opened for only 14 of those days to allow inspection, cleaning and outfitting of the inside. A total of ten Shuttle-based assembly EVAs over the five missions accumulated over 69 hours in connecting the modules, conducting exterior assembly and outfitting objectives and completing several get-ahead tasks in advance of subsequent EVAs. The planned overall level of Shuttle crew EVA operations during the assembly period alone would increase significantly as the station grew. It was expected that planning for the spacewalking programme would be far more challenging and demanding than anything that had been attempted in the previous 35 years. This challenge became known as the "Wall of EVA", to be scaled to get the job done.

Standing Dominoes

The embryonic International Space Station may have been two years old by the time the first resident crew arrived in November 2000, but it was far from complete. It had been planned at the time for the main station to be completed by 2006, but several events would delay that goal. Most notable was the grounding of the entire Shuttle fleet in 2003 following the loss of Columbia and her crew of seven. This underscored the fragility of relying on the Shuttle system to deliver ISS hardware into orbit, but there was no other vehicle capable (or flexible in its resources) of getting the job done. The remaining orbiters were removed from further assembly work on the station pending the resolution of the investigation into the Columbia tragedy and the ISS operated with caretaker (2-person) crews who would maintain the station and try to fit in as much science work as possible until the Shuttle flights resumed. It would be a long pause.

The investigations delayed the Shuttle's return to flight for 29 months. By necessity, STS-114 in July 2005 was a test flight to evaluate new safety and repair techniques, carrying out the recommendations made in response to the findings of the Columbia (STS-107) Accident Investigation Board. It was not an assembly mission, but it was a much-needed logistics flight to the ISS, as was STS-121, a second test flight a year later. The success of those two missions led to the resumption of ISS assembly flights up to 2011, when the remaining Shuttle fleet was retired with the major ISS assembly programme completed.

As one NASA official observed back at the start of the process: "Building the ISS is like stacking a row of dominoes; if one tumbles, it has a knock-on effect down the line. Delays to just one element, or the postponement of a single launch, had serious consequences for the next dozen or so missions. Therefore, after decades of planning and years of cooperation and preparation, successfully getting the first hardware into orbit and into working order under Expedition Zero was both a monumental task and a relief. But this was only the beginning of a long journey to complete construction and keep the station operating safely and productively.

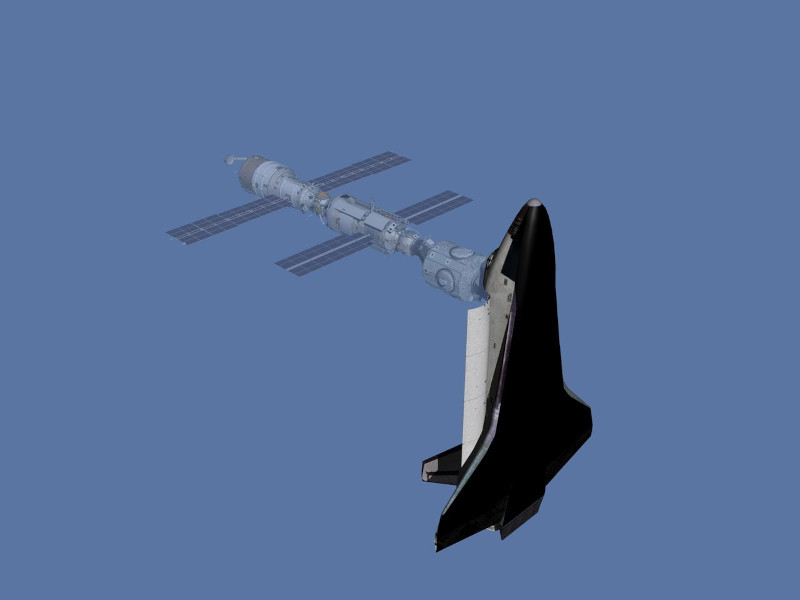

The configuration of ISS during the approach of Atlantis on the STS-106 mission. The recently docked Progress supply vessel is seen at the top, linked to the Zvezda Service Module. This in turn is linked to the Zarya Functional Cargo Block (FCB) and then the US Unity Node 1 module at the bottom.

Double click to edit

Computer-generated artist's impression of the station configuration with the Shuttle docked during STS-106. This mission did not add new modules to the station and was primarily concerned with stocking up supplies in readiness for the first resident crew later in the year.

The STS-106 crew poses aboard the ISS for the traditional in-flight crew portrait. (Clockwise from bottom left) Terrence Wilcutt (pale shirt, CDR), Boris Morukov (MS), Richard Mastracchio (MS), Ed Lu (MS), Dan Burbank (MS), Yuri Malenchenko (MS) and Scott Altman (PLT)

MS Dan Burbank prepares to photograph the departing Inernational Space Station through the overhead windows on the aft flight deck of Atlantis as the STS-106 mission begins its journey home.

MS Ed Lu is photographed by his EVA colleague Yuri Malenchenko as they work on the exterior of the ISS during the sole EVA of the STS-106 mission. The two men were outside the station for over 6 hours on this spacewalk.

Boeing technicians move a Control Moment Gyroscope (CMG) to the Z-1 Truss structure in the Space Station Processing Facility at KSC. The CMG and Z-1 would be carried to the ISS aboard STS-92.

The in-flight crew portrait for the STS-92 crew. (Clockwise from top left) Pamela Melroy (PLT), Leroy Chiao (MS), Michael Lopez-Alegria (MS), William McArthur (MS), Brian Duffy (CDR), Peter Wisoff (MS) and Japanese NASDA (now JAXA)astronaut Koichi Wakata (MS)

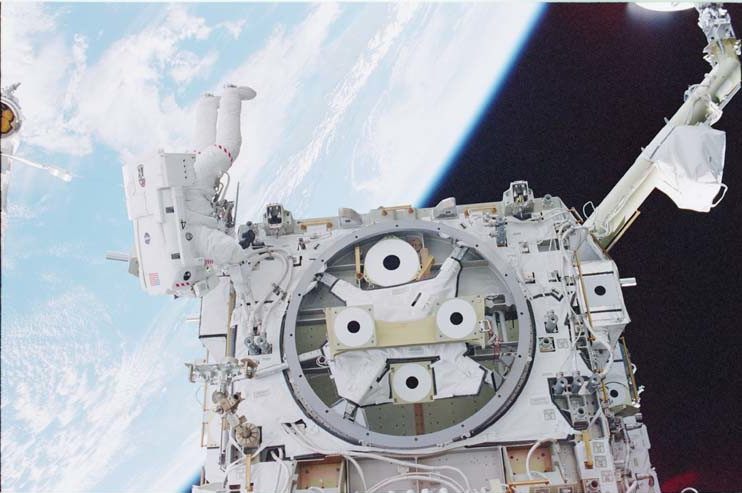

MS Michael Lopez-Alegria is seen working on the Z-1 truss and Node 1 Unity module of the ISS on one of the EVAs performed during STS-92. The astronauts worked outside the station in alternating pairs (Chiao and McArthur, Lopez-Alegria and Wisoff) outside the station for over 27 hours across four spacewalks.

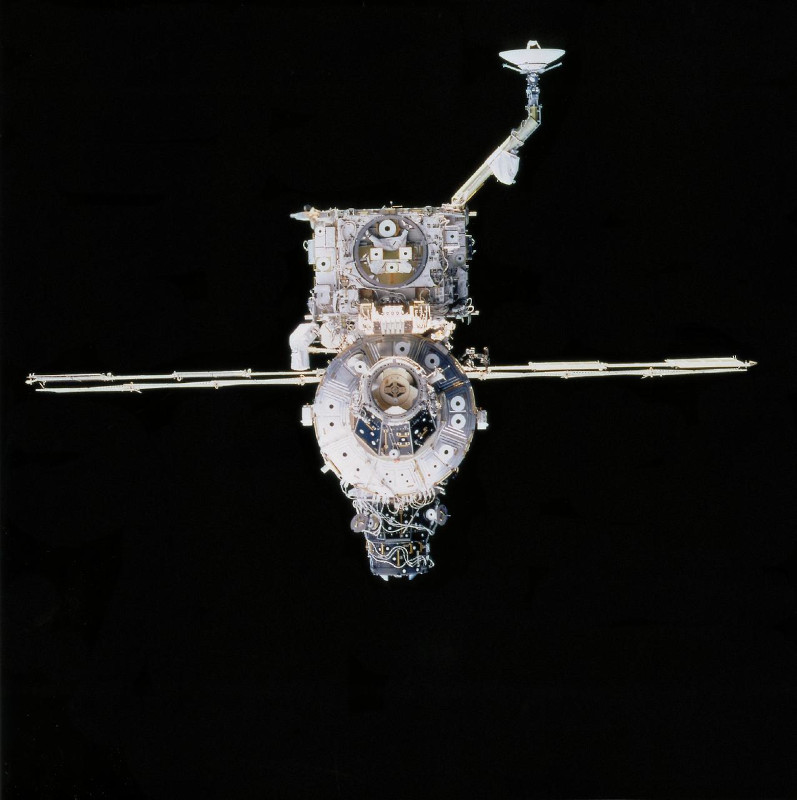

As Discovery departed from ISS at the end of the STS-92 mission, the crew captured this image which clearly shows the new additions to the space station that had been fitted on this flight. Ther Z-1 Truss structure and its antenna are at the top, with PMA-3 at the bottom.

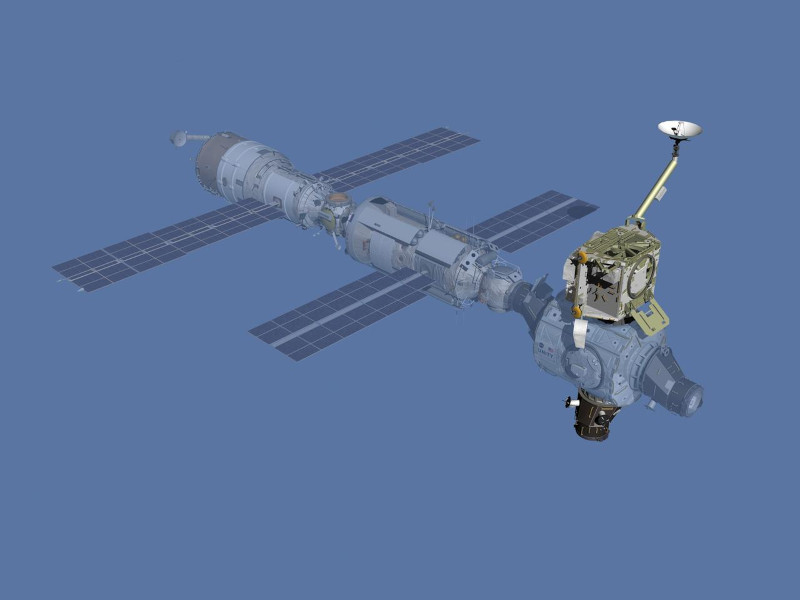

This computer-generated artist's impression of the ISS gives a better overall view of the structure after the STS-92 mission, with the new additions highlighted on the Unity module. There remained much more construction to come over the next few years, but for now the station was ready to receive its first resident crew.

In addition to the mission emblems, each of the Shuttle flights to ISS during Expedition Zero also had its own ISS mission emblem. (From top left) STS-88, STS-96, STS-101, STS-106 and STS-92.